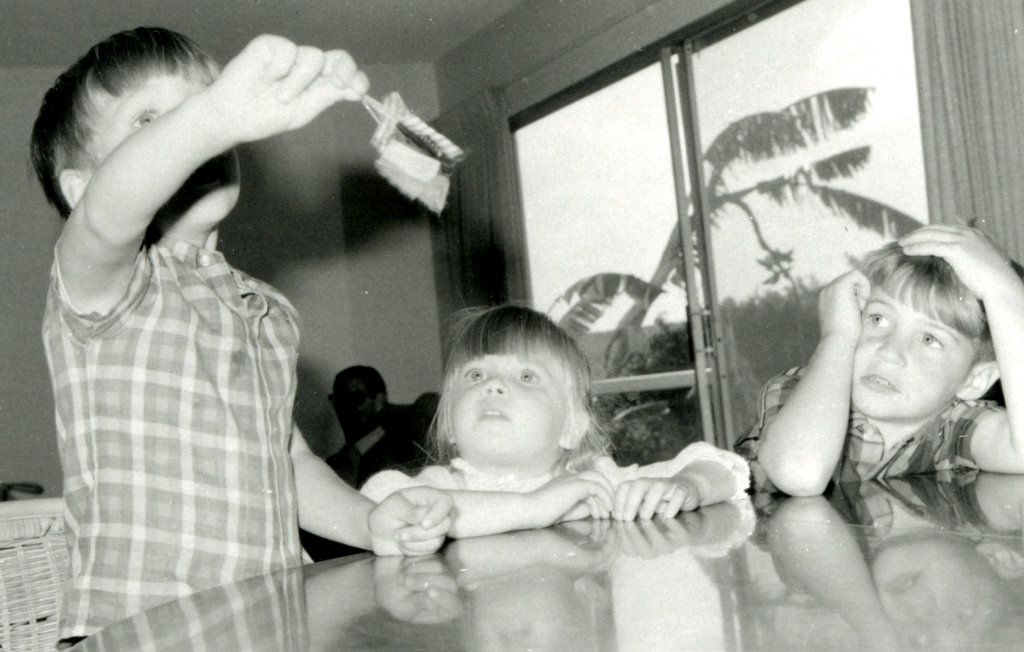

My Brother, Cousin Marcia, Cousin Hugh. Ca. 1969.

My Brother, Cousin Marcia, Cousin Hugh. Ca. 1969.

[Click here to read the beginning of this story. Click here to read its conclusion.]

Walking the Ruins

We pull into the parking lot and panic overwhelms me. I glance at my cousin Hugh in the back seat and see, for the first time, what others see: shaggy beard, rotten teeth, clean but shabby clothing:

He’s a bum.What if they won’t let him in? We’ve come to visit his mother at the nursing home. He hasn’t seen her for five years, because it’s hard to make plans when you live on the streets.

“Let’s pray,” I suggest as we climb out of the car. I hold my cousin’s hand, ravaged by years of needle-borne infections, nearly useless. My other hand rests in my husband, Rich’s, strong, sure grip. He reaches for my cousin, closing our circle. “Father God, you know the hearts of everyone here. Be with us as we go inside.” It’s not much, but it’s all I’ve got. I’m counting on the Spirit to intercede.

As we break our huddle I see Lety, one of my Auntie M’s nurses, walking through the parking lot. “Lety, hi!” I wave. “It’s Sheila, Marlene’s niece,” I remind her as I approach. I don’t visit here as often as I should; I can’t expect Lety to place me, especially from across the parking lot.

I hurry towards her. “That’s Marlene’s son Hugh with us. We’ve brought him to visit her.”

Lety’s eyes light up. “Ooooh, that’s great! I’m on my way out to lunch now. Maybe I’ll see you later.”

Lety would have warned me, I think, if I shouldn’t take him inside. Clinging to that thought, I take a deep breath.

Rich leads Hugh and me through the doors of the nursing home. I smell disinfectant and a faint undertone of urine.

“First we sign in here,” I say to my cousin, too brightly. I write our names on a clipboard. Feeling eyes on me, I notice the nurse at the station closest to the door, watching. “I’m Marlene’s niece, and her conservator,” I say, surprised to hear myself emphasizing my authority. “This is my husband. And this is her son. We’re here to visit.”

I turn to my cousin. “She spends the day mostly propelling herself around the halls in her wheelchair. She always kicks off one shoe . . . the staff calls her Cinderella. Now we just need to find her.”

I feel, and ignore, eyes on us as we make our way down the hallway, checking the dayroom, the dining hall, the corridors.

Rich spots her first, down at the end of the hallway.

I suppress an impulse to grab my cousin, half-expecting him to bolt. Instead he quickens his shuffling pace. He’s about to see his mother. He’s told me that he’s afraid she won’t remember him.

“Auntie M,” I say, “It’s Sheila. I’ve brought the Do-Bee here to see you.”

His childhood nickname draws a flicker from her eyes. She freezes in her chair, stares. My cousin approaches his mother, crouches, reaches for her hand. She wheels her chair around and continues down the hallway. “This is typical, Hugh,” I tell him. “She always does this. We’ll just walk along with her.”

As I turn I see a nurse watching us, suspicious. “Hello,” I tell her. “I’m Marlene’s niece. This is her son. He hasn’t seen her for a long, long time.” I watch her face relax. “I was just about to change her shirt,” she says. “She’s spilled her juice.”

“We’ll wait.”

We stand outside her room and I see the tears on my cousin’s cheeks. I walk to the nurse’s station, ask for tissue. I can’t keep the story inside:

“I’m sorry to bother you, but please, we need some tissue. That’s Marlene’s son here with us today. My auntie–his mom–well, she lost it back in 2000 when her daughter died of an overdose. Her son took care of her for a long time, then Adult Protective Services came to investigate and my mom had to put her in a care facility. And he ended up on the streets . . . he’s an addict, too, like his sister was. He hasn’t seen his mother in five years.”

It amazes me how quickly I can summarize the destruction of an entire family–my auntie’s family. I’m blinking now. The nurse hands me a box of tissue. From some numb place I remember to thank him.

My auntie’s wearing a clean blouse now, and the nurse who changed her wheels her back to us. “Look,” she said, “I’ll put her in the lobby and lock the brake on her wheelchair, then you can sit and visit without having to follow her around the halls.”

In all my visits there, it had never occurred to me to prevent her from rolling, rolling, rolling endlessly through the corridors. My cousin sits, holds his mother’s hand, talks to her. She doesn’t speak. She hasn’t spoken for years.

But she stares at him. She holds his hand. She knows him.

Rich and I are sitting a few feet away, balancing our desire to give privacy against my cousin’s need for support. I hear Hugh telling his mother about people she knows, old friends.

Another resident wheels up, parks herself just a few feet away, and watches my cousin and his mother as if she’s bought a ticket to this show. I look up and around and I see several staff, standing discreetly in the hallway, watching.

They’re smiling, melted around the edges.

I look again at my cousin and my auntie and I see what they see: Not a defeated junkie in tatters visiting a demented, silent woman who would rather be endlessly circling the halls.

It’s not that. It’s a man and his mother, loving each other through everything. Even through this. Especially through this.

It’s holy.

What a wonderful post Sheila! God Bless!

Thanks, Patti. God bless you too!

Thanks for sharing. You have given us such a beautiful picture of Jesus’s heart toward the downtrodden. I felt compelled to pray for your cousin, Hugh, after I read your blog.

Sandy, thank you. That means the world to me.

It brought a tear(actually several). As always, you get to us where we live. Don’t stop the love.

Thanks, Red. I’m grateful.

Sheila,

What a wonderful story of God’s redemptive love. Thanks for sharing. I felt Hugh’s insecurity, your hesitation, but most of all the love. You should tell people to grab a Kleenex before they read this!

Thanks, Ruth. It was an amazing meeting.